One of the most complex issues concerning ancient history is to determine past ways of though and beliefs, especially in the case of the Indus civilization where these must be inferred from material remains, since its writing has not been satisfactorily deciphered. The archaeological indicators here are mainly portable objects of various kinds, figural representations and a few areas within settlements which seems to have been set apart for sacred purposes. There are no structures at Indus sites that can be de described as temples nor are there any statues, which can be considered as images that were worshiped. A few structures reflect a connection between concepts of cleansing through water relation to ritual functions.

The Harappan Civilization (Religious Beliefs)

Last Updated On: 15 August 2023

One of the most complex issues concerning ancient history is to determine past ways of though and beliefs, especially in the case of the Indus civilization where these must be inferred from material remains, since its writing has not been satisfactorily deciphered. The archaeological indicators here are mainly portable objects of various kinds, figural representations and a few areas within settlements which seems to have been set apart for sacred purposes. There are no structures at Indus sites that can be de described as temples nor are there any statues, which can be considered as images that were worshiped. A few structures reflect a connection between concepts of cleansing through water relation to ritual functions.

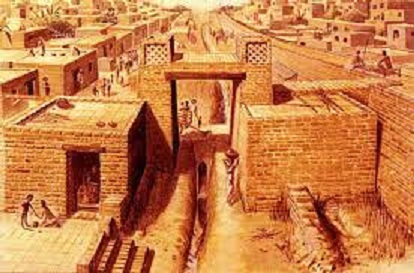

The sunken, rectangular basin known as the Great Bath at mohenjodaro is one such instance. The cult connection of this water using structure is evident from its method of construction which had three concentric zones arount it, including streets on all four sides for the purpose of a ritual procession leading into it. The bathing pavements and well in the vicinity of the offering pits on kalibangan's citable also underline this connection. As for beliefs connected with fertility, it is possible that some terracotta finurines found at Mohanjodaro and Harappa represrent such belief. At towns like Kalibangan and Surkotada, female figurines are practically absent. Even at Mohenjodaro the fact that only 475 of the total number of terracotta figurines and fragments represented the female form means that this was not as common a practice as it has been made out to be. Several of the female figurines were utilized as lamps or for the burning of incense. Fertility in relation to the male principle has also been evoked not merely in the context on the Siva-Pasupati seal but also with reference to the phallic stones that have been found at Mohenjodaro, Harappa and Dholavira as also with regard to a miniature terracotta representation of a phallic emblem set in a ovular shaped flat receptacle from Kalibangan. Religious sancity was associated with particular trees and animals as well. The presence of partly human partly animal characters on Indus seals and a human personage on a pipal tree, in fact suggest a shamanistic component in Harappan religion. None of these features, however suggest a transregional Indus religion with cult centres and stste dominated rituals, of the kind that is writ large on the architectural landscape of Bronge Age West Asia and Egypt.